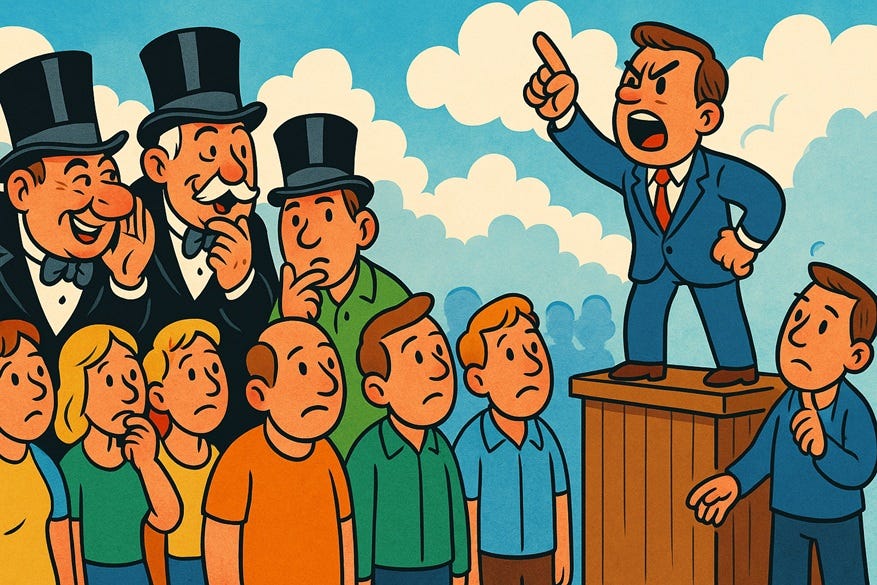

I’ve been asking myself for a while now: Why are so many people today drawn to oligarchs and demagogues? I recently posted this question on Facebook, and the thread that followed was lively and wide-ranging. Here’s my attempt, with some help from ChatGPT, to synthesize those comments — pulling it all together from my own perspective — while acknowledging the many possible explanations and counterarguments raised in that discussion.

Here’s the link to the original Facebook discussion: discussion URL.

1. The Education and Literacy Debate

Several people began by arguing that the problem boils down to a decline in literacy and critical thinking. They suggested that, despite official statistics showing higher graduation rates and more college degrees, true standards have been lowered. In other words, more people have degrees on paper, but those degrees may not reflect the same level of competence or critical thinking they once did.

Counterpoint: Others noted that formal education levels are demonstrably higher than they were in the mid-20th century. If that’s true, the issue may be less about basic literacy and more about a broader failure to think critically — or a cultural decline in intellectual engagement. Yes, more people can read, but that doesn’t mean they’re trained to sift fact from fiction or to handle complex political arguments.

2. The “Lowered Standards” Explanation

Some took the idea of declining literacy further, pointing to a possible “reverse Flynn effect” — the notion that certain measures of intelligence or cultural sophistication may be dipping. They argued that institutional pressures to pass students along could be making degrees easier to earn without equipping people with deeper reasoning skills.

Today’s emphasis on rote memorization and test-taking over analytical thinking and sensemaking, leaves people vulnerable to empty promises and emotional appeals.

3. Dissatisfaction with the Establishment

A recurring theme was that large segments of the population feel disenfranchised, angry, or disappointed with the “establishment” and the “globalist” or “neoliberal” order. In this view, people aren’t ignorant — they’re frustrated and receptive to anyone who sounds willing to break the system. When a populist figure rails against elites, that figure can become a rallying point for those who feel the status quo offers them nothing.

This sense of betrayal drives not just so-called “hayseed rubes,” but also well-educated or formerly middle-class individuals, to back candidates who might otherwise seem outlandish. They see it as a protest vote or a last-ditch effort to make their voices heard.

Dismissing everyone who votes for a demagogue as undereducated or gullible misses the larger story: many are simply fed up with feeling left behind.

4. Oligarchs, Wealth Concentration, and the Global Cycle

Some noted that super-wealthy elites have been funneling more and more of the world’s wealth into their own hands. This extreme concentration of wealth can provoke admiration, resentment, or a strange mix of both.

Some view a billionaire business mogul as a folk hero — a strong figure who’s “successful” and therefore able to manage national affairs. Others see that figure as a symbol of inequality. But in times of economic anxiety, a wealthy figure who promises to protect the people from other elites can paradoxically appear appealing.

Counterpoint: Not everyone is impressed by these oligarchs. Many see them as part of the same rotating cast of exploiters. Whether people trust them depends on how convincingly they pose as outsiders.

5. Religious or Ideological Vacuum

Some comments suggested that as traditional religion loses its grip, people look for something else to fill the moral or spiritual void. A charismatic leader — oligarch, demagogue, or both — can step into that gap.

Expansion: Several noted that religious conservatives support politicians who hardly embody traditional religious values. Why? Because if someone promises to appoint judges or enact policies aligned with conservative goals, voters may overlook moral failings.

Counterpoint: Others pointed out that religion isn’t fading everywhere — some communities remain devout. Rather than a spiritual vacuum, it may be a broader crisis of trust, authority, or identity that drives people to dominant leaders.

6. Fear, Distrust, and Information Overload

Fear and distrust of institutions — government, media, academia — came up frequently. People described it as “chronic fear,” “overwhelm,” or “filter overwhelm.” In the age of social media, misinformation spreads fast. Coupled with distrust of experts, a loud, confident voice can seem authentic — or like the people’s champion.

Some pointed to Facebook itself (ironically, in a Facebook thread) as a culprit: its algorithms amplify sensational, emotionally charged content, creating a siege mentality. In that setting, a demagogue’s black-and-white worldview can feel reassuring.

Counterpoint: Others argued that this is nothing new — demagoguery has always thrived where fear and distrust exist. What’s different now is how quickly — and globally — those messages spread.

7. “Systemic Fatigue,” or the Fourth Turning

A few referenced broader cycles like the “Fourth Turning,” the theory that society evolves in recurring generational phases, each ending in crisis. According to this view, we’re simply at that crisis juncture — a time ripe for extremes and strongmen.

Over the past few decades, neoliberalism — capitalism favoring deregulation, global trade, and financialization — promised prosperity but often left people behind. When any grand system fails to deliver, extreme alternatives start to look appealing.

Counterpoint: Others cautioned against over-interpreting cycles. Human nature may be constant; it’s economic and social conditions that change, making demagogues more or less palatable depending on the moment.

8. Promise Fatigue and Lack of Real Leadership

Several comments pointed to “promise fatigue.” One administration after another makes bold promises — on growth, health care, education — yet glaring problems persist. This breeds cynicism toward traditional leadership and openness to more radical voices.

When traditional political leaders fail to address root issues like wage stagnation, student debt, or the opioid crisis, people are primed to listen to someone claiming to have real answers — especially if that person isn’t “part of the game.”

9. It’s Human Nature, or “Continuous Invariant”

One person challenged the premise of my question altogether, arguing that our susceptibility to strongmen is simply part of human nature. From this angle, nothing about these times is unique — demagoguery is a constant in sociopolitical life.

Counterpoint: Others insisted something new is afoot: the speed and scale of digital information (and misinformation), and historic levels of wealth inequality. Demagoguery may be ancient, but today’s environment is particularly fertile for it.

10. Summing It All Up

After surveying these perspectives, here’s what I think is happening. The draw to oligarchs and demagogues doesn’t stem from a single cause. Rather, it’s a confluence:

- Exhaustion with broken promises and cynicism toward traditional political leadership

- Distrust and dissatisfaction with academic, cultural, and economic elites

- Emotional and informational overload fueled by digital media

- A sense of powerlessness or a lack of clear moral or cultural anchors

- Growing wealth disparities that lead people either to admire or to loathe the super-rich