Exploring the Ozarks :: A Bioregional Journey

The stream you see at the top of this article was my lifeline. I am here because of her clear waters, rippling chimes of natural music, and the deep calm I felt playing in her flows as a child. Welcome to Joy Creek.

Penny and I took Elise to visit my family in the Ozarks. This ancient terrain stands out as a plateau of highlands that break the otherwise endless flatness of the Great Plains. Rocks formed as sediments that drifted to the seafloor of a long-ago ocean that split the North American continent. Over hundreds of millions of years these sandstones, limestones, and other remnants of ancestral life pushed upward and then were carved out into one of the most vast networks of caves to be found on Earth.

Ozarks Plateau that spans Arkansas, Missouri and Oklahoma

With more than 7,600 registered caves it is no surprise that Missouri’s official slogan is The Cave State. The subterranean flows of water define so much about this unique landscape. It was thus a natural starting point to visit Meramec Caverns as our entry into the bioregion.

We broke up our drive from the Chicago Area with a tour of this 16 mile long cave system. It was profound to walk along an underground river to discover the stalagmites and stalactites formed by dripping water across the span of tens of thousands of years.

Water flows in the underground river of Meramec Caverns

Penny had never seen the “aliveness” of a living cave like this one. She was deeply affected by the rock formations we found there. Standing pools of water with mineral deposits dripping from the ceiling onto rising columns of rock below.

This is a cave that took four hundred million years to form. The accumulation of sediments. Continental uplift to form a mountain range. Slow erosion to wear it away and leave a plateau behind. Then the infiltration of water to open cavernous pathways and deposit minerals in the rocks.

A room full of mineral formations in Meramec Caverns

These ribbon-like folds are the minerals left behind as crystal waters flow into the underground river. The first lesson about the Ozarks is that its most important movements take place underground. You won’t find the secrets of this landscape without learning about what is happening below your feet where your eyes are blinded by the darkness.

In the late 1970’s there were a series of bioregional congresses that started in the Ozarks. They continue today with 45 of them in total thus far. Local people have a pragmatic resilience in part because it is so rural and remote in this part of the continent. I grew up on a chicken farm in the heart of the Ozarks. It has shaped my existence in subtle ways that Penny could see because she knows me so well.

Our second day brought us to a place where I camped, hiked, and fished as a child. Roaring River State Park is the home of one of the largest fish hatcheries in the United States. People come from all over the world to fish its waters. The millions of rainbow trout grown here each year are transported to rivers more than a thousand miles away.

This is an exemplary place for feeling the conservation efforts that preserve river health. It is a symbol of the industrial era as a model for large-scale food production that includes “wild caught” fish that get restocked into rivers and lakes by hatcheries like this one.

Rainbow Trout that restock the rivers of North America

What few people know is that these central highlands hold a legacy of river conservation that is a hallmark of field ecology, management of fisheries, and public education in the form of recreational activities.

The Ozarks hides in plain sight with underground rivers and caves together with wildlife management approaches that have huge impacts in far-off places. These elements combine in a very literal way when we discover that the hatchery is fed by spring waters that flow out of a cave that has an unknown depth.

Roaring River’s hatchery sits at the mouth of a spring that is at least 450 feet deep. Divers have yet to find its bottom and one of them tragically died last year in the most recent attempt to discover where the end might be.

The spring at Roaring River State Park

Part of our visit to the Ozarks was to show my daughter where her daddy grew up. This brings us back to that stream in the photograph at the top of this post. Joy Creek was my sanctuary as a child. I would venture out into the woods when someone bullied me or when I just needed precious healing time to myself.

It was this little stream that sustained me through the darkest times. My nature connection flows with the churgling waters of Joy Creek. Taking Penny and Elise to see it was such a profound experience for me now that I’m an adult.

It warmed my heart to see Penny at Joy Creek

So much of my life is about bringing dead rivers back to life. It has been more than twenty years since I visited Joy Creek. My return brought a flood of emotions that tell me where my desire to restore rivers was probably born.

If a river kept me alive through years of depression, perhaps restoring dead ones today can give my child the resilience she will need for all that lies ahead. You can see how deeply I still feel this connection today.

Offering my blessings to the stream that held my youth

I had forgotten how important this place was during my childhood. A few minutes of walking would bring me from our front door to spots like this one where I caught crawdads by hand and hooked my share of worms trying to get the blue gill to bite my fishing line.

Today I just want to let the cool waters tingle my fingertips and enjoy seeing Elise fall in love with her daddy’s sacred stream. She sat and offered a song to the river while my heart swooned.

Elise singing a blessing at Joy Creek

Now that we are the guardians of Las Albercas in Barichara, I can feel the depth of my heart’s connection that threads Joy Creek with the lands of South America. Very different landscapes. Very different cultures. And yet the love of a child singing health to waters flows between them in a father’s heart.

I will cherish these moments for the rest of my life.

The house where I grew up

Most people don’t know that I lived in a cave as a child — or rather, that our house was underground like a Hobbit hole. You can see the house today in the photo above. Note how the roof is a rounded mound of dirt. I was a cave person who loved flowing streams.

Such a child of the Ozarks!

Visiting a Civil War era cemetery in the woods

Another theme from this landscape is death. So much violence happened here. During the Civil War there were more battles in Missouri than all the rest of the United States combined — more than 20,000 battles took place in the span of four years.

Part of the quiet history of those times is that slave owners in the Ozarks didn’t like that Missouri entered the Union as a “free” state. No slaves allowed. So they relocated to Plano, Texas where a mythology was born claiming the South never lost the war. The infamous Klu Klux Klan grew from this displaced community. I grew up in Klan country with profound racism that still exists to this day.

A mass grave from the Civil War with 47 tombstones

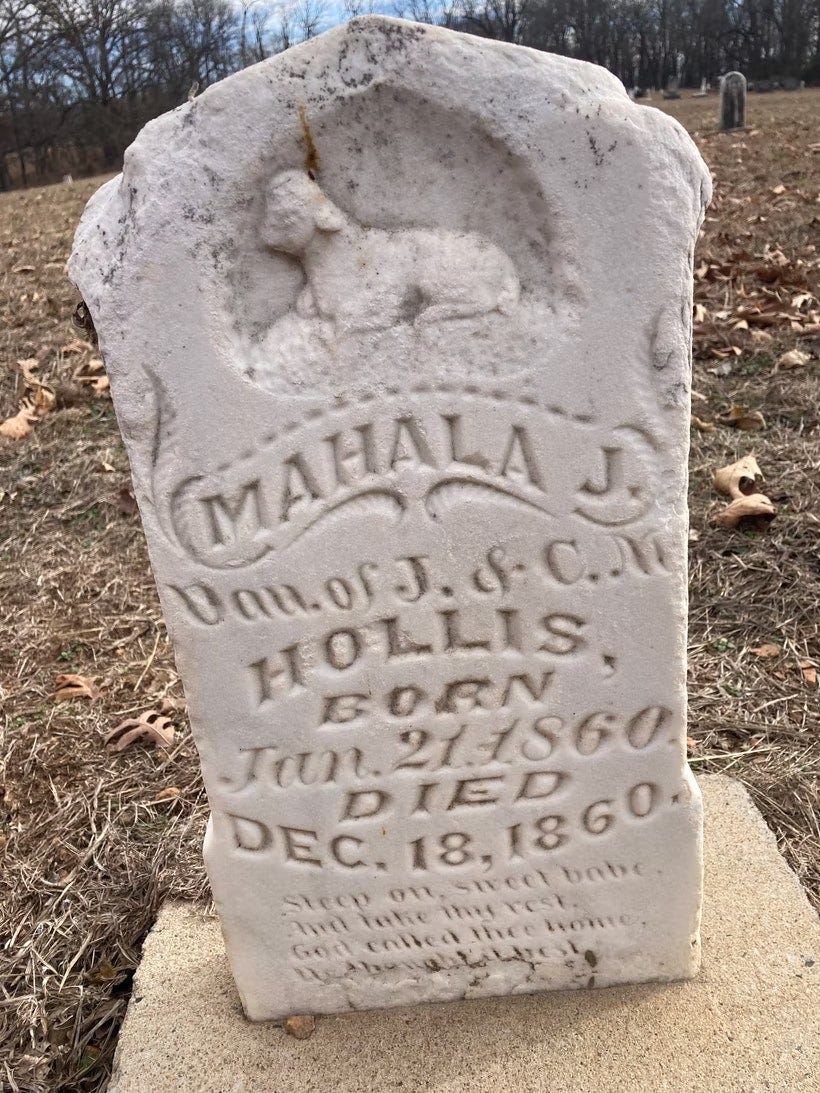

This little cemetery is in the woods a few minutes walk from the farm where I grew up. I spent countless hours visiting these graves to inquire into the spiritual depths of life and death. What did it mean for so many youth to die during an historic war in the mid 1800’s?

An entire section of the cemetery is devoted to children. One grave is a child who died at birth. Another was less than a year old. Hints of disease and health challenges. This is a landscape that was harsh and difficult. The indigenous peoples were forcefully removed. Settlers and homesteaders arrived to farm the land. Many died while toiling for their survival.

Tombstone of a child who died very young

Cultural history plays a huge role in the regeneration of a bioregion. The Ozarks will need to reckon with its violent history if it is to restore peace deep within its darkest recesses. Myth and lore still carry many a conversation late into the night for the honest people of Missouri.

As we left the Ozarks, it felt important to hold the bizarre history of Manifest Destiny and Westward Expansion together with cultural genocide of indigenous peoples. We ventured into Gateway Arch National Park to look down upon the cityscape of St. Louis.

Getting ready to “climb” the Gateway Arch

St. Louis is known as the gateway to the west. It plays an important role in the history of the United States — and the larger narrative of “progress” that has included the rape and pillage of landscapes across the globe.

I was disappointed to learn that the story in the historical museum still downplays the rightful place of native peoples. Yet it was heartening to see that they allowed the “manifest” destiny to be questioned in one of their exhibits.

Haunted by ghosts of the massacred natives

We departed from the Ozarks with a clear sense that there is much to learn from this distinctive landscape. At the convergence of two primary rivers, the great Missouri and Mississippi, we could feel the story of place change when we drove off into the flatlands of Illinois on our return voyage.

One thing we carried with us was a sense that I am deeply shaped by my upbringing in the Ozarks. It shapes the pragmatic honesty expressed through my authentic struggles with depression, ongoing dynamics of collapse, and the need to do what I can to help regenerate landscapes across our precious home planet.

May this sharing bring insights to you about how we can weave bioregions and learn from their unique ecological and historical contexts.

Onward, fellow humans.

If you feel moved to help birth a planetary network of regenerative bioregions, please consider supporting us on Patreon or make a one-time donation on Paypal.

Tagged with :