Faced with accelerating disruptions and social and environmental breakdowns, traditional forms of philanthropic giving may be less effective than they once were. Confronted with societal divisions, wars, and the climate crisis, core actors in philanthropy have begun to ask how philanthropy can respond more effectively in moments of a polycrisis. How can philanthropy deal with new forms of hypercomplexity? What is the role of philanthropy in responding to breakdown, and how can it promote regeneration and transformation?

Numerous experiments and innovations in the philanthropic sector are responding in various ways to these disruptive challenges — from trust-based funding to participatory grant-making to flexible multi-year core grants for transformative infrastructure building.

Underlying these innovative efforts is a desire to create systemic and long-lasting impact that leads to a transformation of existing patterns, and that supports sustainable and inclusive change for the well-being of communities and the planet.

Three Types of Complexity

In our work at the Presencing Institute we believe that most solutions to the challenges we face already exist. But what is missing is our collective capacity to implement these solutions in a timely way and at scale. We also believe that the role of philanthropy is shifting. Traditional forms of charity and donor-defined problem-solving can provide effective solutions to straightforward challenges, but the new complexities of the polycrisis require new approaches from all sectors. There are implications for (a) the relationship between philanthropy and social change makers and for (b) the awareness and mindsets that guide philanthropic activity.

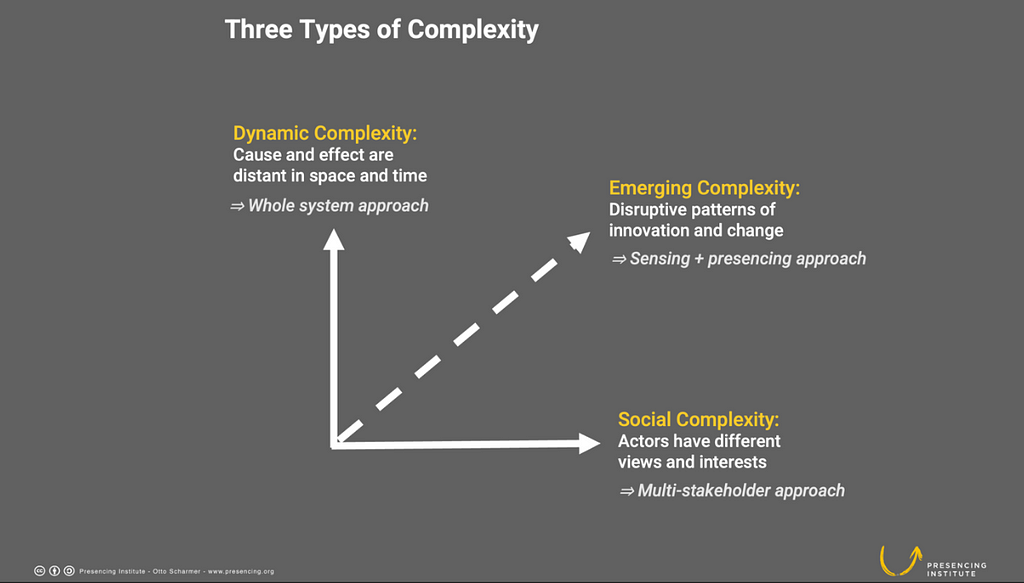

The discipline of systems thinking can help us to understand complexity. Three types of complexity play into the challenges that our institutions and communities face (see Figure 1).

Dynamic complexity concerns delayed feedback loops: cause and effect are distant in space and time. For example, carbon emissions from past decades in distant places have an impact on the climate across the globe. Dealing with this type of complexity involves the use of whole systems methodologies (e.g., system dynamics).

Social complexity concerns differences in views and interests: a variety of stakeholders bring different interests and worldviews to a situation. One recent example was the attempt by the COP 28 stakeholders to agree on a joint statement. Dealing with social complexity successfully requires using refined multi-stakeholder methodologies to bring together diverse interests and viewpoints in collaborative problem solving.

Emerging complexity is the defining feature of the pressing challenges facing our planet, our institutions, and our communities: disruptive challenges whose solution is unknown, in part because the problems keep changing and evolving. Examples of this kind of complexity range include technology (AI), health (Covid 19), war, terrorism, structural violence (e.g., in the Middle East), and climate-related disruptions. Dealing with emerging complexity requires a systems view rather than a silo view. For example, the Paris Agreement only a few years after the collapse of the climate talks in Copenhagen showcased how an awareness- and systems-based approach to leadership can shift the thinking of the respective stakeholders from an egosystem view to an ecosystem view. Doing this new leadership work effectively requires methods and tools for transformative systems change.

Four Types of Philanthropy

In summary, philanthropy today faces, like everything else, increasing levels of complexity. These challenges present opportunities for innovative responses. The following matrix outlines how four types of philanthropic activity respond to systemic complexity. In reality, concrete examples of philanthropic giving may blend elements of more than one of these types. But to clarify the different types (and their underlying logic), it may be helpful to look at the table below.

Philanthropy — literally, love for humanity — has traditionally taken the form of charitable and individual giving (Philanthropy 1.0). The challenge is defined, and the donor helps. A community needs a library, a school needs a gym, or individuals need food and shelter. A recipient might acknowledge a gift by naming a space after a large donor or publishing the names of smaller donors. These gifts meet an immediate need but usually do not eliminate the root causes of the problem. Root causes may include poverty, inequality, exclusion from opportunity, systemic racism, and climate destabilization to name a few. Addressing the systemic issues that led to the problems requires a different type of response.

Philanthropy 2.0 introduces measurable outputs and outcomes and aims to increase the efficiency and impact of the giving. A foundation might develop a strategic focus (such as reducing CO2 emissions, reducing class size, or improving access to health care) and an indicator system that measures the impact of giving in those areas.

The recent popularity of effective philanthropy has demonstrated that working with quantifiable indicators has efficiency advantages, but it also assumes that the philanthropist knows what the problem is and how to best address it. Critics of this approach point out inherent power imbalances and biases toward impact areas that are easily measurable in the short term as well as a lack of accountability on the side of the philanthropic decision makers. For example, US philanthropy gives out $500 billion a year and European philanthropy gives about $60 billion a year. What is society’s return for the tax advantages that the wealth holders receive on the $560 billion? Is that investment moving us towards a better world by addressing some of the deeper root issues of these problems, or are these investments (and the trillions of dollars in financial assets which generated them) just perpetuating the root causes that created them?

Philanthropy 3.0 is more collaborative, experimental, and long-term, and it includes the perspective of the grantee to a larger degree. For example, the community-based foundation Maine Initiatives is an innovator in participatory grant making. Local communities not only define the focus areas of their giving but also decide who will receive grants. In 3.0 Philanthropy the relationship between the philanthropy and the change maker is collaborative. Dialogue is central to its success, and giving is embedded in specific social contexts.

Funder collaboratives, donor-advised funds, and impact investments are other types of experiments with 3.0 philanthropy with elements of moving in direction of 4.0. The Lankelly Chase Foundation, for example, has created a “transition pathway” for dismantling itself and moving its assets into communities who can use these assets in any manner that they see fit. As the foundation’s CEO Julian Corner said: “We got stuck and realized we are part of the problem.”

Philanthropic activity that moves into the direction of 4.0 is defined by an intention of systems transformation and usually shows characteristics such as trust based relationships, larger multi-year grants, capacity building, and involving the entire ecosystem of partners. These same characteristics without the intention of systems evolution or transformation would not qualify for 4.0.

Other organizations in the 3.0 space that begin to move in the direction of Philanthropy 4.0 include the Dutch Postcode Lottery and the Ford Foundation. The Dutch Postcode Lottery provides unrestricted institutional core funding to Dutch and international NGOs to support key civil society organizations, and helps them to strengthen their eco-system of collaboration. The Ford Foundation’s BUILD program (Building Institutions and Networks), a 5-year, $1 billion initiative, aims to strengthen the capacity of civil society organizations to create civic infrastructures. These examples are significant in the current context where civil society organizations in many countries have been under attack.

Systemic root issues tend to be less measurable and often require longer-term interventions. Reducing structural violence, institutional racism, or environmental destruction requires the voices of the entire system in devising solutions.

Philanthropy 4.0 is an emerging form of philanthropic activity that focuses on transformative systems change. 4.0 philanthropy aims to address the root causes of a challenge by taking a whole system perspective. The guiding goal of 4.0 philanthropy is to seek transformations that generate flourishing and prosperity for all. For example, the Eileen Fisher Foundation works to move the apparel industry toward “regenerative fashion design”; the company Eileen Fisher Inc. innovates in that same space. Doing so requires a process that allows a microcosm of that system to see and sense and redirect itself towards emerging future possibilities.

A different example that moves into the direction of 4.0 concerns a maternal health project in Namibia, that was supported by the Presencing Institute. The intervention focused on a microcosm of the local health system: from governmental health officials to nurses. Working closely with mothers and local groups, the health care system was able to identify and implement systemic solutions to improving maternal and child health. A shift in culture helped the system establish new institutional structures and become more responsive to the needs of mothers and their children. This was possible because the grant makers that supported this project accepted the “not-knowing-all-the-answers” approach and the radical involvement of the social system on all levels of the process.

What would have been elements that could have made this a full blown 4.0 project? More focus on the social determinants of health (inequality, differentials in health outcomes by race) and wellbeing.

Other examples focus on building cross-sector transformative leadership infrastructures, including u-lab and IDEAS. In u-lab, a free online, multi-local capacity-building platform in systems change, more than 240,000 registered users from 186 countries went on an innovation journey during the past nine years. In IDEAS, in collaboration with a foundation partner in South East Asia, United in Diversity, we have supported infrastructures that bring leaders from business, government, civil society, and academia on a joint journey of understanding the root issues in their system and prototyping solutions addressing them. What’s interesting about both these examples is that the most important systemic impact only becomes visible years after.

Philanthropy 4.0 not only changes the relationship between philanthropy and grantees from transactional to transformative; it also requires a new form of shared awareness and intention that allows all partners in the system to adapt and co-evolve as needed. Philanthropy, when guided by a 4.0 view, also aligns its investment side with the impact it wants to generate.

Complex Problems Require Complex Solutions

Which type of philanthropy is best? It depends. For known problems with known solutions at a moderate level of complexity, a 1.0 or 2.0 way of operating works because it is efficient. But in contexts that are defined by disruption and/or by emerging complexity — that is, in environments with evolving problems and evolving solutions — a different approach is called for. More sophisticated 3.0 and 4.0 philanthropy reflect this new context of societal change. Complex challenges require complex solutions. Addressing them with 2.0 giving would be, as a colleague from the United Nations put it recently, like trying to “get to the moon using a donkey cart.”

Philanthropy 3.0 and 4.0 differ from 2.0 by giving the grantee freedom to respond flexibly in the face of fast-changing environments and disruption. We were fortunate to have that freedom in March 2020, when Covid hit and much of the world moved into lockdown. It took us at the Presencing Institute only a few days to mobilize a core team to provide a critical sense-making space for our community. Over the course of a few months, roughly 15,000 people participated regularly in bi-weekly online gatherings, using deep listening, stillness, and awareness-based social practices to make sense of the disruption and to reimagine and reshape their own journeys forward. That intervention, called the GAIA Journey (Global Activation of Intention and Action), has led to numerous place-based initiatives that continue to generate change today. Our actions were entirely made possible by a trust-based grant that let us put together a program that we believed would serve the community’s needs.

Shifting the Locus of Philanthropic Action Upstream

Stepping up philanthropic activity at the 4.0 level requires shifting the impact focus of philanthropy from downstream (short-term metrics) to upstream (evolving and transforming mindsets and operating systems).

These evolutions require an inquiry into the root causes of the challenges we face. An amazing number of change makers worldwide are pursuing these inquiries. But they often must operate in isolation and frequently lack the methods and tools to approach transformative change more consciously and more collectively.

What we’ve learned over the years is that the success of a transformational process in a system is a function of two things: one, a shift in mindset of the people who are enacting these systems; and two, a supporting infrastructure that helps these change makers to navigate that journey. These supporting infrastructures have been the enabling condition for movements around the world (from the decolonization movement in India, the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, the civil rights movements in the United States in the 1960s and in Eastern and Central Europe in the 1980s, etc.). Behavioral and transformational change needs an intentional support structure. Civil society and cross sector initiatives often lack these high quality support structures.

The current polycrisis and wave of systemic breakdowns cannot be solved by the same thinking that created them. Philanthropy 4.0 tackles systemic challenges at their root by shifting the locus of intervention from downstream (outcome-driven) to upstream (operating with new mindsets and operating systems) including:

- Scalable institutional infrastructures that bring together all relevant players to co-shape the evolution of the system.

- Co-creative leadership capacities for shifting awareness from a silo to a systems view — i.e., from ego to eco.

- Methods, tools, and spaces that support new collaborative and co-creative capacities.

All of these components exist, at least in the form of seeds and prototypes. What’s missing is the supportive environment — the soil, the nutrients, the water, the light — that allows these seeds and prototypes to grow, to connect, and to become operational collectively. Shifting the primary locus of change in philanthropic action from merely downstream to also upstream could provide a much-needed boost to transformative change initiatives that help to realign intention with action at the level of the whole system.

I thank Saskia van den Dool-Gietman, John Heller, Antoinette Klatzky, Emma Paine, and Katrin Kaufer for their feedback and valuable input, as well as a network of interviewees who volunteered their time.

Philanthropy 4.0: What Form of Giving Enables Transformative Change? was originally published in Field of the Future Blog on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Tagged with :